The Many Faces of Kamishibai (Japanese Paper Theater): Past, Present, and Future

This article was written by Tara M. McGowan, an artist, storyteller, and teacher, who has studied and worked in Japan for nearly a decade. She received her PhD in the Reading/Writing/Literacy division of the Graduate School of Education at the University of Pennsylvania in 2012. Her book The Kamishibai Classroom: Engaging Multiple Literacies through the Art of ‘Paper Theater’ (2010) is a handbook for teachers to create and perform kamishibai stories with students, and her forthcoming book Performing Kamishibai: An Emerging New Literacy for a Global Audience (2015) examines the potential of kamishibai as a format for teaching multimodal literacies through student performance in public schools.

When first introduced to kamishibai, most Americans hear about the street-performance artists who typically sold candy or treats to crowds of children on busy urban street corners in Japan from the early 1930s until the 1950s when the arrival of television all but extinguished this unique form of popular culture. This is the image of kamishibai that award-winning illustrator Allen Say has eloquently memorialized in his picture book Kamishibai Man (2005). But what many people do not know is that street (gaitō) kamishibai was just one of several varieties of kamishibai that flourished in Japan in the years leading up to and during World War II. In 2015, as we observe the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II, the history of kamishibai offers a rare opportunity to reflect on why and how so many different types of kamishibai emerged and flourished during this turbulent time in Japanese history.

Before we can understand the important role kamishibai played during the war years in Japan, it will be helpful first to trace kamishibai’s origins. Japanese scholars have offered a broad range of possible historical precursors for kamishibai from emaki picture scrolls to shadow theater to mechanized peep shows (nozoki karakuri). [1] Although kamishibai is often described as a manifestation of Japan’s long and rich tradition of etoki (picture explaining), which can be traced back to the 10th century when Buddhist picture scrolls were narrated by itinerant priests and nuns (Kaminishi), it would be misleading to argue that this makes kamishibai an “ancient” art form. Kamishibai is actually a relative newcomer to the etoki tradition in Japan, and, as kamishibai artists and historians, Kata Kōji (1971) and Kako Satoshi (1979) have argued, the only precursor that can be traced unequivocally to the development of kamishibai is the 18th century magic lantern show or utsushi-e.

Kamishibai is often described as a uniquely Japanese medium, but it is doubtful that it would have developed in the form that it did without an ingenious remixing of several media from both inside and outside Japan. Even during Japan’s more than 200 years of isolationism during the Edo period (1600-1868), technologies from the outside world trickled into the country, particularly through ongoing trade with the Dutch. Magic lanterns—an early form of slide projector, which used glass slides placed in front of kerosene lamps as a light source—was a popular form of entertainment that spread around the globe in the 18th century. In Japan, several portable lanterns (furo) were used in performance simultaneously so that an array of colorful characters and scenes could be animated at the same time by manipulating the slides in various ways and projecting them onto a wall in a darkened room (Figure 1).[2] Performances became so elaborate that they were referred to in the western part of Japan (kansai) as nishiki-kage-e or “brocade shadow pictures,” inspired by colorful wood-block prints (nishiki-e) of scenes or actors from kabuki plays and by popular forms of shadow theater (kage-e). In the eastern part of Japan (kantō), they were known as utsushi-e (slide pictures) because the animation was achieved by sliding a series of images of the same character depicted in motion quickly through the projector (Figure 2). This feature is what makes the magic lantern a precursor of film, or moving pictures.

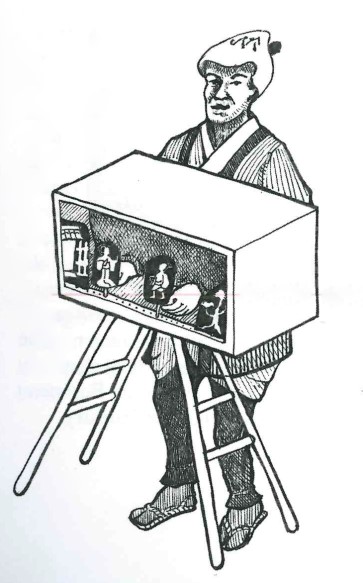

Figure 1, An utsushi-e performer, holding a Japanese-style magic lantern. The lamp or light source is inside the box on his shoulder.

Figure 2, A magic-lantern slide showing the animation. By moving the slide quickly before the light, the character appears to engage in sword fight.

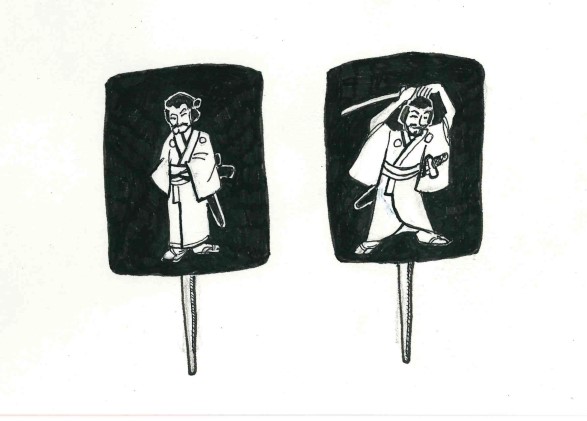

Utsushi-e performances in Japan were spectacular, and they required the coordination of several skilled performers, who were adept at handling dangerous, flammable equipment in darkened interiors.[3] In the early 1900s, a man by the name of Hagiwara Shinzaburō, popularly known as Shin-san, came up with a new method of animation based on techniques from magic lantern shows. Shin-san created a paper puppet on a stick that depicted a character in one position, but when flipped around quickly showed the same character in a different position, giving the same impression of movement as in the animation of the magic lantern slides. The extraneous background of the figure was colored in black so that when the puppet was manipulated against a black curtain inside a portable wooden stage, only the animation would stand out in sharp relief against the background (Figures 3 and 4). The advantage of this new form of theater was that it could be performed by one person in a lighted room or even out of doors with no danger of fire. Shin-san tried performing this “new magic-lantern show” (shin-utsushi-e) in the usual venues,[4] but customers were unimpressed. They accused him of offering them cheap theater made of paper—in other words, “paper-theater” or kamishibai!

Figure 3, An example of a samurai warrior tachi-e puppet.

Figure 4, A tachi-e performer and portable stage.

The name stuck, and Shin-san took his form of kamishibai to the streets where it gained in popularity. This kamishibai later came to be known as tachi-e, or standing pictures, to distinguish it from hira-e (flat pictures) that we normally recognize as kamishibai today. Tachi-e style kamishibai offered miniaturized versions of the hugely popular kabuki and bunraku puppet theater productions of the time, and, like the magic-lantern performances, the stories were composed of sensationalistic highlights from popular dramas on the big stage. Tales of unrequited love, revenge, double suicide, and ghost stories proliferated. A network of rental companies emerged so that storytellers could take turns performing one episode of a story at a time, while making efficient use of a limited number of hand-made materials. This kashimoto (rental) system enhanced the spread of both the tachi-e type of kamishibai, as well as the new kamishibai that developed later.

Hira-e: The New Kamishibai

Because of their often sensationalistic content, street performances of all kinds were subject to frequent bans by the authorities, and kamishibai was no exception. In 1929, when tachi-e was undergoing a ban, three street performers in Tokyo (Takahashi Seizō, Gotō Terakura, and Tanaka Jirō) put their heads together to develop a new form of picture-storytelling that they hoped would enable them to pull the wool over the authorities’ eyes. By 1930 they had created the first story entitled The Palace of Fantasy (Mahō no goten, artist: Nagamatsu Takeo; story: Gotō Terakura; other sources cite the title as Otogi no goten). They dubbed this new form of storytelling “new picture-stories”(shin e-banashi) to make it appear innocent and harmless, but their audiences were not so easily fooled and took to calling it kamishibai.

This new form of kamishibai emulated visual techniques from yet another global medium that had taken audiences in Japan by storm—silent film. In Japan, early films were rarely “silent” because film narrators, called katsudō benshi, regularly entertained audiences with soundtracks that they performed orally (Dym). Kamishibai storytellers emulated this popular style of verbal performance while they manipulated their illustrated cards inside a small wooden stage. Just like the miniaturized kabuki stories of the earlier era, this new kamishibai provided miniaturized versions of what audiences could see on the big screen. Moving pictures would eventually edge out magic lantern shows, much as television eliminated the demand for gaitō kamishibai street performances several decades later.

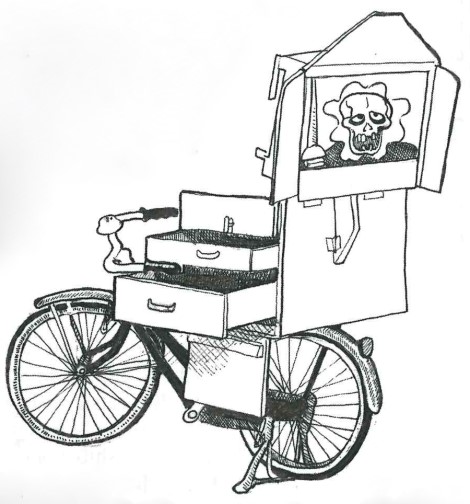

Like the tachi-e stories of an earlier generation, the new kamishibai offered stories in episodic format that left audiences hungry to hear more.[5] The storytellers would sell treats to their young clientele prior to the performances and make sure that the stories they told were suspenseful enough to get them to come back the next day and the next. Both stylistically and in terms of subject matter, the street-performance kamishibai of this period can be dubbed the true predecessor of present-day animé, where virtuous adolescent heroes typically are called upon to save the world from adult corruption or, alternatively, futuristic threats from alien monsters. Popular series from the period carried such titles as Shōnen Taigā (Tiger-boy) about a Tarzan-like youth or The Prince of Gamma about a boy-hero from outer space. Always desperate for new material to meet the daily demand for sensationalistic stories, kamishibai artists culled inspiration from every imaginable source, including Japanese folk legends about shape-shifting foxes, popular Japanese chanbara films about fighting samurai warriors and ninjas, and Western classics like Peter Pan and Frankenstein. The most popular series by far was titled Ōgon batto (The Golden Bat) , which centered on a red-caped skeletal superhero who saved the day, usually in the nick of time (Figure 5). The episodes from this series continued over three years, beginning in 1831 and were revived after the war. It was even made into an animated series for television. When television first entered Japan, it was popularly called denki kamishibai (electric kamishibai), no doubt because of its similarity in size, shape, and function to the kamishibai screen.

Figure 5, A gaitō kamishibai-ya’s bicyle and a close-up of Ōgon batto

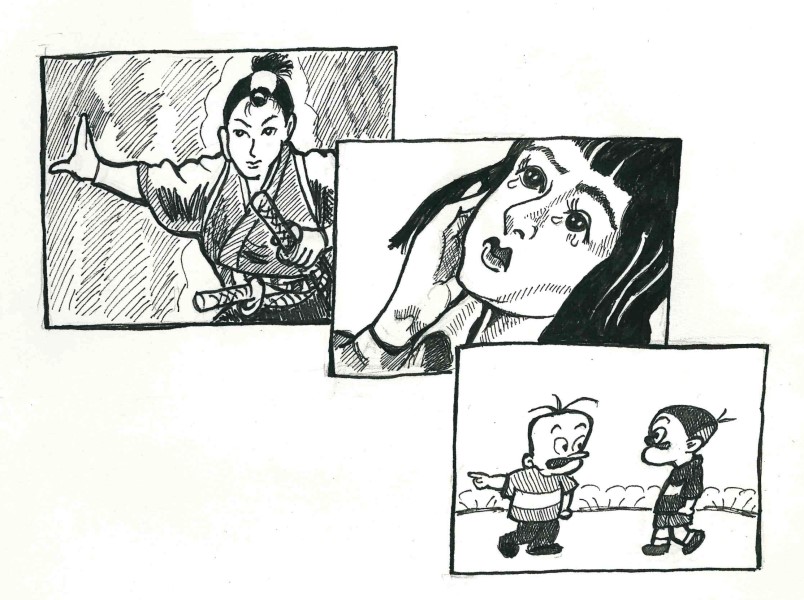

Typically, street performances offered episodes of stories in three genres that covered the emotional spectrum: exciting action adventures, like The Golden Bat; sentimental tear-jerkers, often about abused or orphaned girls; and light-hearted comic (manga)cartoons (Figure 6). In between episodes of these stories, the storytellers would test the wits of their audiences by offering prizes for quizzes involving verbal and visual puns or rebuses. Winners of these contests could win even more treats. Preparing hand-drawn episodes and quizzes for this range of genres on a daily basis kept the street-performance artists so busy that they didn’t have time to write scripts for the stories on the backs of the cards. Usually, the storytellers who rented out the candies and stories from the kashimoto (rental establishment) would orally relay the highlights of the next episode to the storyteller who would then rent out that episode the following day. It wasn’t until 1938 that the authorities demanded the stories be written on the backs of the cards so that they could monitor content. Even then, the text was limited to the barest of outlines. It is important to remember that prior to this regulation kamishibai was primarily an oral-visual storytelling form that involved a liberal amount of improvisation. It was not until the advent of published educational kamishibai that reading written scripts or text verbatim from the backs of the cards became the common practice that it is today.

Figure 6, Examples of katsugeki action adventure (top), namidachōdai tear-jerker (middle), and manga cartoons (bottom).

Published Educational Kamishibai

In the early 1930s, Japan was suffering from a world-wide depression that sent the unemployed from all walks of life into the streets. With few other options, many became gaitō kamishibai performers. The new hira-e style of kamishibai did not require extensive training, and almost anyone with a bicycle, a stage, and a voice could set up in the trade. Soon, there were as many as 30,000 street-performers roaming urban neighborhoods throughout Japan. It did not take long for educators, parents, and government authorities to begin looking at this new kamishibai with deep suspicion. The overwhelming popularity of the new kamishibai meant that large crowds of unsupervised children were gathering on busy street corners, creating potentially hazardous conditions. The treats the kamishibai performers offered were handled without any apparent concern for sanitation, and the garish colors used by the street-performance artists were thought to be too stimulating for children. Finally, the questionable backgrounds of the performers and the lurid content of the stories were considered inappropriate fare for young audiences. There were frequent calls for banning street-performance kamishibai altogether.

Not long after the “new kamishibai” was invented, a Christian social worker by the name of Imai Yone returned to Japan having spent several years training as a missionary in the United States. Imai began teaching Sunday school classes but soon discovered that many of her would-be pupils cut class as soon as they heard the clappers (hyōshigi) announcing the arrival of the kamishibai man. When she followed her students out into the streets, she immediately recognized kamishibai as a powerful and mesmerizing medium for communication that could be adapted to her purposes of spreading the Christian faith. She hired kamishibai artists to create dramatic stories from the Bible, such as the story of “Noah and the Flood,” “The Good Shepherd,” “David and Goliath,” and “Daniel in the Lion’s Den.” Imai emulated the rental system of the street performance artists so that her stories could reach a wide audience.[6] By 1933, she had organized a troupe of performers called the “Kamishibai Missionaries” (kamishibai dendō dan) and had co-founded the Kamishibai Publishing Company (kamishibai kankō kai).

Imai made several significant innovations to the kamishibai format. She increased the size of the cards to what we now consider the normal size for the standard kamishibai stage (10 ½ X 15 inches), nearly double the size of the cards used by street performance artists. She wrote complete scripts for the stories that could be read from the backs of the cards with instructions for how they should be performed, and she developed kamishibai stories with images that could be published in journal format. These pages could be taken out, colored in, and glued to stiff cardboard so that they could be assembled and performed even in remote areas of Japan. Although Imai wrote the scripts for the stories herself, she commissioned street performance artists to create the images for her stories because she recognized that their flamboyant, cinematic style would make the Bible stories come to life for young audiences. These stories are also sometimes referred to as Gospel Kamishibai (Fuku-in kamishibai).

Inspired by the success of Imai’s Christian kamishibai stories, a children’s magazine publisher by the name of Takahashi Gozan began a company called Zenkōsha to publish Buddhist parables, such as “The Buddha and the Pigeon” (Oshakasama to hato) and “The Festival of the Ancestors” (Tamamatsuri). Trained at an art academy in visual design, Gozan consciously distanced himself from the sensationalistic style of the street performance artists and drew instead upon the visual vocabulary and color palette of Disney cartoons, producing in kamishibai format such world-wide classics as “Little Red Riding Hood,” “Alice in Wonderland,” and “The Tale of Peter Rabbit” (Figure 7). Gozan’s preferred audience was very young children, and he was particularly active in promoting kamishibai training for day-care centers and kindergarten teachers. Since Gozan’s time, the visual vocabulary of published educational kamishibai has been drawn both stylistically and in terms of subject matter increasingly from the world of children’s book illustration rather than film, making it difficult for 21st century audiences to perceive how kamishibai could be considered a precursor of manga or animé.[7]

Figure 7, A simplified rendering of a scene from Takahashi Gozan’s “Tale of Peter Rabbit.”

When one of Imai’s missionaries performed kamishibai for a group of Tokyo University students who were volunteering at a site constructed to help victims of the 1923 Kantō earthquake, a student in the Department of Education named Matsunaga Kenya immediately recognized kamishibai’s potential uses in the context of the classroom. Anxious to improve the lot of the children of the “proletariat,” Matsunaga created a kamishibai story called “A Guide for Life” (Jinsei no annai), based on the first Russian talkie to enter Japan. The story centered on the plight of vagrant children who, through hard work, were able to better themselves. Matsunaga went on to teach and write for the journal “The School of Life,” and, again inspired by Imai Yone, published his kamishibai stories in magazines so that they could be colored in, pasted to cardboard, and performed anywhere in the country. He was the first to promote what today is called tezukuri (hand-made) kamishibai, where his students created and performed their own stories to achieve what Matsunaga called a “comprehensive life education” (sōgōteki seikatsu kyōiku) (Suzuki 55). Matsunaga also wanted to improve the reputation of the street performance artists and recruited them to form a coalition to promote the use of educational kamishibai in schools at all grade levels. In 1938, Matsunaga and his colleagues formed the Educational Kamishibai Federation of Japan.

Kokusaku (Government Policy) Kamishibai

Without this increase in publishers of educational kamishibai, it is unlikely that Japan’s militaristic government would have called upon kamishibai to play such a pivotal role as a media for propaganda in the build up to World War II. By the beginning of World War II (1941-1945) and middle of the second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945), published kamishibai like all other media had come under the control of the government censors, and the stories had to closely align with the policies set forth by the Imperialist government. Whereas the gaitō street-performers had freely adlibbed and interacted with audiences, with government policy kamishibai, performers were required to read the text on the backs of the cards precisely as written. No longer were the performers of kamishibai enlisted from the unemployed and disenfranchised on the margins of society. Instead, teachers and local authorities were trained to read the government sanctioned kamishibai verbatim. Audiences were expected to listen in respectful silence because any interaction might suggest political unrest.

Although the emergence of government policy kamishibai greatly restricted the freedom of the performative aspects of kamishibai, it also led, conversely, to an unprecedented flourishing of kamishibai genres for all ages. Kamishibai were no longer limited to sensational episodic stories for urban children of low-income families. With government backing, the number of educational kamishibai publishing houses increased to eighteen (including the companies started by Imai, Gozan, and Matsunaga described above), and by 1942, the total number of published editions of the stories reached 825,800 (Suzuki Sensō no jidai desu yo! 2). This is all the more extraordinary when one considers the governmental restrictions on paper-use at the time.[8] Government officials clearly recognized that the intimate audio-visual format of kamishibai, which had mesmerized audiences on the street corners, made it a much more effective medium for communication than any number of dry newspaper articles or lectures. Unlike radio or film, both of which were also highly effective media for propaganda, kamishibai did not require electricity or expensive equipment. It could be readily transported to even the most remote areas of Japan or the occupied territories.

Kamishibai became the medium of choice for spreading the government sanctioned history of the Emperor’s divine lineage and for convincing audiences both inside and outside Japan—in China, Korea, the Philippines, and Indonesia—of the inevitability of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. Stories were developed to placate audiences in the languages of the occupied territories and to comfort soldiers at home and abroad. There were kamishibai made to instruct communities on how to build bomb shelters and what to do in case of air raids. As kamishibai historian and street- performance artist Suzuki Tsunekatsu has argued, kamishibai functioned during this period much like textbooks in a national classroom, and they were particularly effective at galvanizing the emotions of all levels of society in both urban and rural communities around a common cause (Suzuki Media toshite no kamishibai 70) .

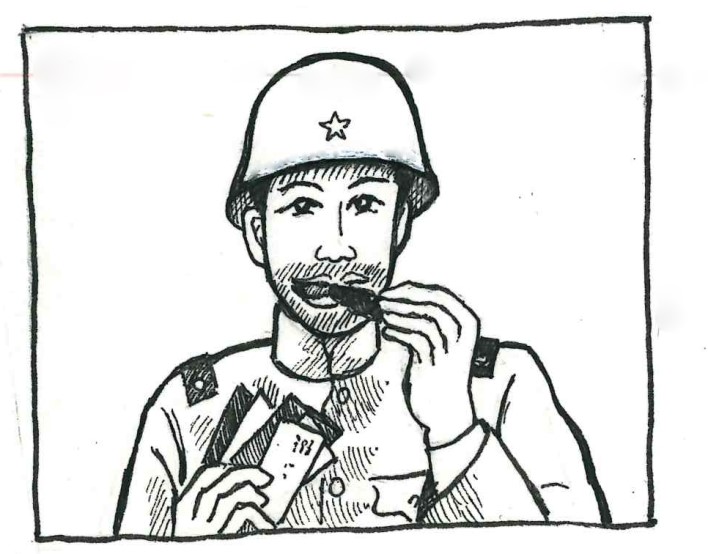

To a surprising degree, government policy kamishibai tended to emphasize the tragic but touching sacrifices of soldiers over their glorious achievements or victories. Many of the stories ended with the soldiers’ heroic deaths and stressed how the news of their loss worked to strengthen the resolve and spirit of sacrifice of other family members back home. In one notable example, titled “Chocolate and Soldiers,” a father sends chocolate candy wrappers from where he is stationed in China back to his wife and children, who use them to convince the candy company to send chocolate as a consolation to the soldiers on the battlefront. Just as they are about to achieve their goal, they receive word of their father’s death, and the story ends with the mother encouraging her son to follow in his father’s noble footsteps (Figure 8). Virtuous mothers played a central role in many of these stories, as in the government policy kamishibai “The Comb.” In this story, a mother single-handedly brings up her two sons from their youth. Because they are poor, she sells her one precious belonging—a comb—to purchase the uniform her oldest son needs to take part in the national sports day at his school. Years later, when her son is fighting on the battlefront in China, he sends her a comb with a letter, reminding her of her sacrifice for him and ending with the line “Mother, do you know why the Japanese Army is so powerful? It is because we are all thinking of our mothers” (Suzuki 80). The strength of kamishibai as a tool for propaganda lay in the immediacy of the dialogue and vividness of the imagery, which made these simple but emotionally gripping stories appear to unfold before the audiences’ very eyes.[9]

Figure 8, A scene from “Chocolate and Soldiers,” depicting the father in uniform, happily eating a chocolate bar.

Post-War Kamishibai

The use of kamishibai for propaganda during World War II made it an object of particular scrutiny when the war ended. General Douglas MacArthur and the Allied Powers were anxious to purge Japan of its former Imperialist ambitions, and kamishibai performers after the war had to get their stamp of approval. Nonetheless, people turned once again in droves to gaitō kamishibai for many of the same reasons that they had before the war—poverty, displacement, and a desire to forget ones immediate suffering. Street performance artists quickly reorganized to fill the demand for cheap entertainment. Whereas there had been an estimated 30,000 street-performance artists before the war, the numbers nearly doubled to over 50, 000 in the years following. Instead of candy, the storytellers would scrounge around for any food items they could make or sell. Since most urban centers in Japan had been the targets of bombing, few pre-war kamishibai cards survived, but many of the popular series were revived after the War. Japan’s alliance with its former enemies made American popular genres, such as the Western, newly available. Kamishibai artist Kata Kōji illustrated new episodes for The Golden Bat (Ōgon batto) series, but now the superhero was depicted as a figure of peace, combatting enemies, who looked and dressed very much like Nazi soldiers. The popularity of street performance kamishibai would not wane until the 1960s when an increasingly affluent Japanese middle-class could afford to buy televisions and keep their children entertained sitting in private living rooms rather than standing on public street corners. By the 1970s and 80s, kamishibai was increasingly viewed in Japan as a medium from a backward and painful era that most people were anxious to forget.

Meanwhile educational published kamishibai had become a firmly established presence in schools for students of all ages. Artists developed “democratic kamishibai,” which taught people how to exert the rights of citizens in a democratic nation, and anti-war kamishibai, such as the best-seller Heiwa no chikai (“A promise of peace” by Nagata Shin and Ineniwa Keiko 1952), became required reading. Kamishibai were developed to teach almost any subject, from history and literature to ethics and music. There were kamishibai biographies, chronicling the lives of such famous figures as William Tell, Thomas Edison, the poet Matsuo Basho, and Helen Keller. The war years had expanded the possible genres for kamishibai to almost any topic imaginable, and the text printed on the backs of the cards, indicating how the stories were to be performed, made it possible for teachers and students alike to read the stories aloud with little preparation or training. Kamishibai continued to be an expected feature of most Japanese classrooms until 1967 when the Department of Education implemented a 10-year plan to overhaul text book requirements. Under this ruling, kamishibai were considered expendable goods and were no longer required. Not surprisingly, the number of kamishibai publishers, which had been steadily declining since the War, plummeted with this new policy. Today, there are only two prominent publishers of educational kamishibai in Japan—Dōshinsha and Kyōiku-gageki—a marked drop from the 18 publishers active during the war years.

Although the presence of kamishibai has diminished both as a street-performance art and in public school classrooms in Japan, it has made advances in other areas since the War. In 1952, through the efforts of Kako Satoshi and Takahashi Gozan, among others, kamishibai was dubbed a Children’s Cultural Treasure (Jidō bunkazai), and its use in kindergartens and preschools flourished as never before. This has led to the unfortunate impression in Japan that kamishibai is a medium only for the very young. Another area of growth in kamishibi in Japan has been in the grass-roots tezukuri (hand-made) kamishibai movement. Throughout Japan, in community centers and libraries, people of all ages create and perform hand-made kamishibai, and kamishibai storytelling festivals are held annually or biennially in various parts of Japan. Many of these stories adapt local legends from oral tradition or folklore to the kamishibai format.

The post-war folklore movement has led to a burgeoning of published folklore in Japan in both picture-book and kamishibai formats. These stories have been translated and exported to other parts of the world to the point that many people outside Japan think that kamishibai is a medium primarily for telling Japanese folklore. In an ironic twist, this quite recent development in the history of kamishibai may account for the prevailing misconception that kamishibai is an ancient storytelling form because so many folktales are set in an indeterminate Japanese mukashi, or “long ago,” past. Folktale classics like “Issun-bōshi” (The One-Inch Boy), “Kasa Jizō” (Hats for the Jizos), or “Momotarō” (The Peach Boy) do come out of an ageless oral tradition, but their incarnation as kamishibai can be traced back as recently as the 1960s and 70s.

The Globalization of Kamishibai

Perhaps the biggest growth in interest in kamishibai as a format is happening outside Japan. Artists and kamishibai practitioners involved in the tezukuri kamishibai movement have actively been transporting kamishibai to countries throughout Asia and the middle-east to encourage local artists to create their own stories. Gaitō street performance artists have toured throughout the world, inspiring street-performers from England and Australia to Spain and Peru to construct stages for the backs of bicycles and emulate the gaitō style of kamishibai performance. Animé and manga fans the world over are becoming interested in kamishibai as a precursor of these globally popular visual media. In New York, Margaret Eisenstadt and Donna Tamaki of Kamishibai for Kids have made Japanese kamishibai cards available in English translation, and Moon Leaf Arts: Story Card Theater in California publishes their own smaller versions of the kamishibai cards and stage. In France, Callicéphale has published kamishibai for several decades, and other European publishers, such as Bracklo in Germany and Paloma in Switzerland, have also emerged in recent years. IKAJA (The International Kamishibai Association of Japan), which is supported by the publisher Dōshinsha, has been particularly active in spreading the word about kamishibai through its newsletter, which is published in Japanese, French, and English, and it now claims a membership in more than 30 countries worldwide.

It is in this context of increasing global interest in kamishibai that a review of the history of the format is particularly valuable. By looking at the history of kamishibai, we are reminded that the kamishibai format does not have to be limited to one definition, performance style, or audience but rather should be seen as a truly versatile format that is limited only by the imagination. As the history of kamishibai demonstrates, methods of kamishibai performance, the visual vocabulary of the stories, and even the size and shape of the format have shifted over time to serve different agendas and purposes, and these shifts will continue to occur as kamishibai travels outside Japan and is adapted for different cultural venues and audiences. It is this almost limitless adaptability that makes kamishibai an exciting and vital communicative format that will continue to motivate artists, storytellers, and educators in their respective communities to create new kamishibai performances into the future.

My own particular interest as an educator, artist, and storyteller is in the tezukuri (hand-made) kamishibai movement and the opportunities that kamishibai offers students of all ages to cultivate their literacy skills through the creation and performance of their own original stories. It is this aspect of kamishibai that I examine in depth in my forthcoming book Performing Kamishibai: An Emerging New Literacy for a Global Audience (2015). Through workshops and residencies in classrooms and libraries, I have developed techniques for teaching students to perform their own kamishibai stories, and I have come to see kamishibai—much as Matsunaga Kenya described it more than 70 years ago—as a marvelous instrument for education, the full potential of which has yet to be realized. The curriculum that I provide here with this article aligns with the Common Core Curriculum Standards and may be adapted for any content area. It is my hope that kamishibai will continue to challenge artists and storytellers the world over to develop mesmerizing new stories for audiences of all ages and that teachers will engage students in authentic learning experiences (Matsunaga’s “comprehensive life education”) by providing opportunities for them to perform their own original kamishibai stories for family, teachers, and friends.

[1] As with any history, there are many variations on the story of how kamishibai came to be. What I am presenting here is a distillation of several histories written by prominent kamishibai scholars in Japan (see bibliography).

[2] All pen and ink illustrations for this article are my own.

[3] As Figure 1 demonstrates, performers in Japan would carry magic lanterns on their shoulders so they could move freely about the room.

[4] The venues for this kind of performance were known as yose, which were similar to vaudeville theaters in the West, where an eclectic array of performers from rakugo (comic storytellers) to joruri (puppeteers) could showcase their talents.

[5] It should be noted that the tachi-e style of kamishibai did not immediately die out with the advent of film. One of Kata Kōji’s first memories is of making a tachi-e puppet of Charlie Chaplin’s silent film The Kid. Voice-over artist and kamishibai performerUte Kazuko, whose father had been a gaitō kamishibai performer, remembers that he also trained performers on how to use a tachi-e style stage.

[6] It should be noted that around the same time in the Western part of Japan (kansai), Nishizaka Tamonori was creating hand-made kamishibai for the Christian organization called the Sunday World Company (Nichiyō sekai sha).

[7] This is what makes books like Eric Nash’s Manga kamishibai: the art of Japanese paper theater (2009) such a valuable resource for kamishibai audiences outside Japan, who may otherwise never have a chance to see examples of street-performance kamishibai cards.

[8] As a way to make optimal use of paper, kamishibai artist Takahashi Gozan developed kamishibai stories incorporating origami and collage techniques that are still popular among tezukuri (hand-made) kamishibai artists today.

[9] For an in depth discussion of how kamishibai works as a particularly persuasive and affective medium, see Chapter Four of Performing Kamishibai: An Emerging New Literacy for a Global Audience (McGowan, forthcoming).