Making Literary History: A Tribute to Donald Keene

Japan Society has hosted many literary luminaries over the years, but no other person could have paved the way for Japanese literature and culture to flourish in the 21st-century world as well as Donald Keene. Japan Society’s 1955-56 Annual Report noted that “The Society has underwritten and will sponsor during the coming year Donald Keene’s Anthology of Japanese Literature, due to be published this autumn.” The next year, Grove Press released the companion volume, Modern Japanese Literature, with both works attracting high praise from critics. In April 1984, Prof. Keene gave a talk at the Society in celebration of the publication of his definitive history of modern Japanese literature, Dawn to the West, speaking “with great authority and gentle humor on the 15 years he spent writing and researching the two-volume work that totals over 2,000 pages.” A frequent lecturer at Japan Society over the years, Prof. Keene served on its Board of Directors from 1976 to 1982. In 2006, Prof. Keene received the Japan Society Award for his outstanding contribution to better U.S.-Japan understanding. The Donald Keene Center of Japanese Culture at Columbia University is named in his honor.

Donald Keene (1922-2019) was Professor Emeritus and Shincho Professor Emeritus of Japanese Literature, Columbia University at the time of his farewell evening at Japan Society on June 13, 2011, shortly before he moved to Japan to finish out his life. Without Professor Keene’s work as a scholar of both traditional and modern Japanese culture, the history of Japanese literature in English, and indeed, outside of Japan, would look very different.

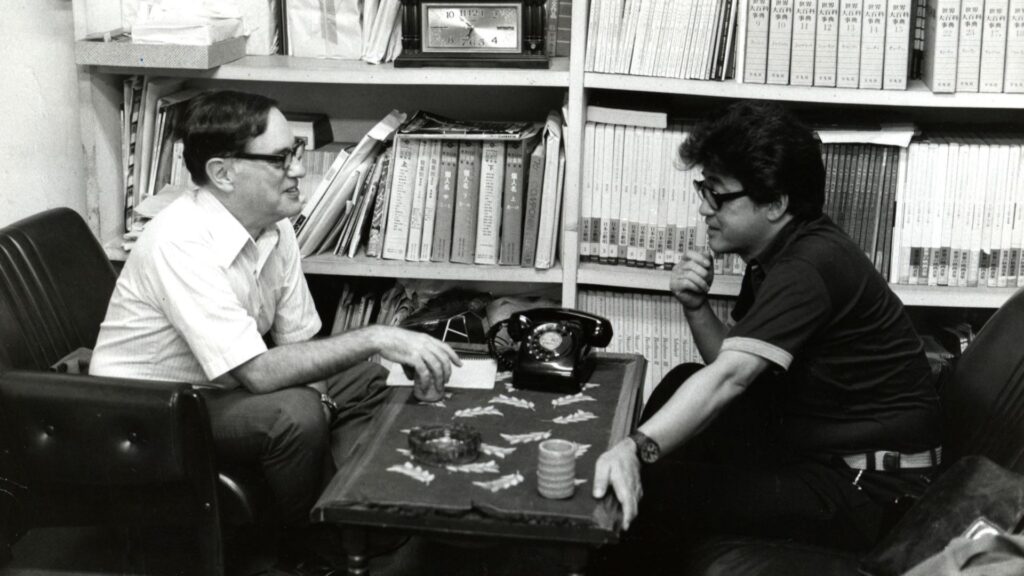

Excerpts from Prof. Keene’s interview with novelist and playwright Kobo Abe in August 1978, published in the December 1978 Japan Society Newsletter:

Keene: What led you to write your first play?

Abe: It was an accident. I had no intention whatsoever of writing a play, but I had no choice. It happened rather early in my career as a writer. I was asked by a magazine for a short story, but somehow I couldn’t manage to write anything. As the deadline approached, I became more and more frantic. At the time I still had trouble selling my stories, and I was worried that if I failed to meet the deadline I would never again be asked for another. The night before the deadline I was absolutely desperate, when suddenly it occurred to me that it might be easier to work out something if all I had to do was write dialogue, and I didn’t have to go to the trouble of writing descriptions and the rest. I threw away everything I had written up to then, and in a great hurry composed a piece consisting entirely of dialogue. It took about three hours. This was my first play, called The Uniform …

Keene: You are best known abroad as a novelist, rather than a dramatist. Of course, there are translations of your plays into English, Russian and other languages. But are your plays as important to you as your novels, or is writing plays a secondary accomplishment?

Abe: I certainly do not think of it as a secondary accomplishment. As far as I am concerned, my plays are as necessary and as important as my novels. But I don’t think of my work in the theater as being confined to writing plays. Most playwrights have traditionally felt that their responsibility ended when they delivered a finished play to the producer, but I do not distinguish all that much between a play and the performance. In my case it is not so much a contract between writing plays and novels as between working in the theater and writing novels. Both have the same importance. If either was missing from my life it would bother me …

Keene: Sometimes you dramatize stories you have written in the past. In such cases do you adopt a different attitude towards the materials? Or do you consider that the text of a play—as opposed to a performance—is much the same as a story?

Abe: I feel that they are quite different. Adapting a story for the stage seems less like the dramatization of an existing story than being stimulated into writing something quite distinct. If I were doing this to the story of another writer it would be unforgivable, but since I am doing it to my own work, I feel I can forgive my lack of respect for the original.