Kurosawa: Scenes and Episodes

Director Kurosawa on the set of Seven Samurai, award-winning 1954 epic film.

October 9th marks 40 years since Japan Society Film (then known as the Japan Film Center) launched the first complete, English-subtitled retrospective on Akira Kurosawa in 1981. This brief reflection by noted Japanese film scholar Donald Richie was originally published in Japan Society’s September 1981 newsletter in anticipation of the Kurosawa retrospective and subsequently included in the series’ program book. The article is presented now as it was originally published in 1981. It is accompanied by newly scanned images from Japan Society Film’s Archives.

Kurosawa: Scenes and Episodes

By Donald Richie

Donald Richie has been acquainted with Kurosawa for more than thirty years. He has watched the unfolding of Kurosawa’s development as one of the world’s great directors, he has translated many of his scripts, and he has written the most penetrating and sensitive analyses of his films. The following reminiscences are excerpted from the program book published by the Japan Film Center for the Kurosawa Retrospective.

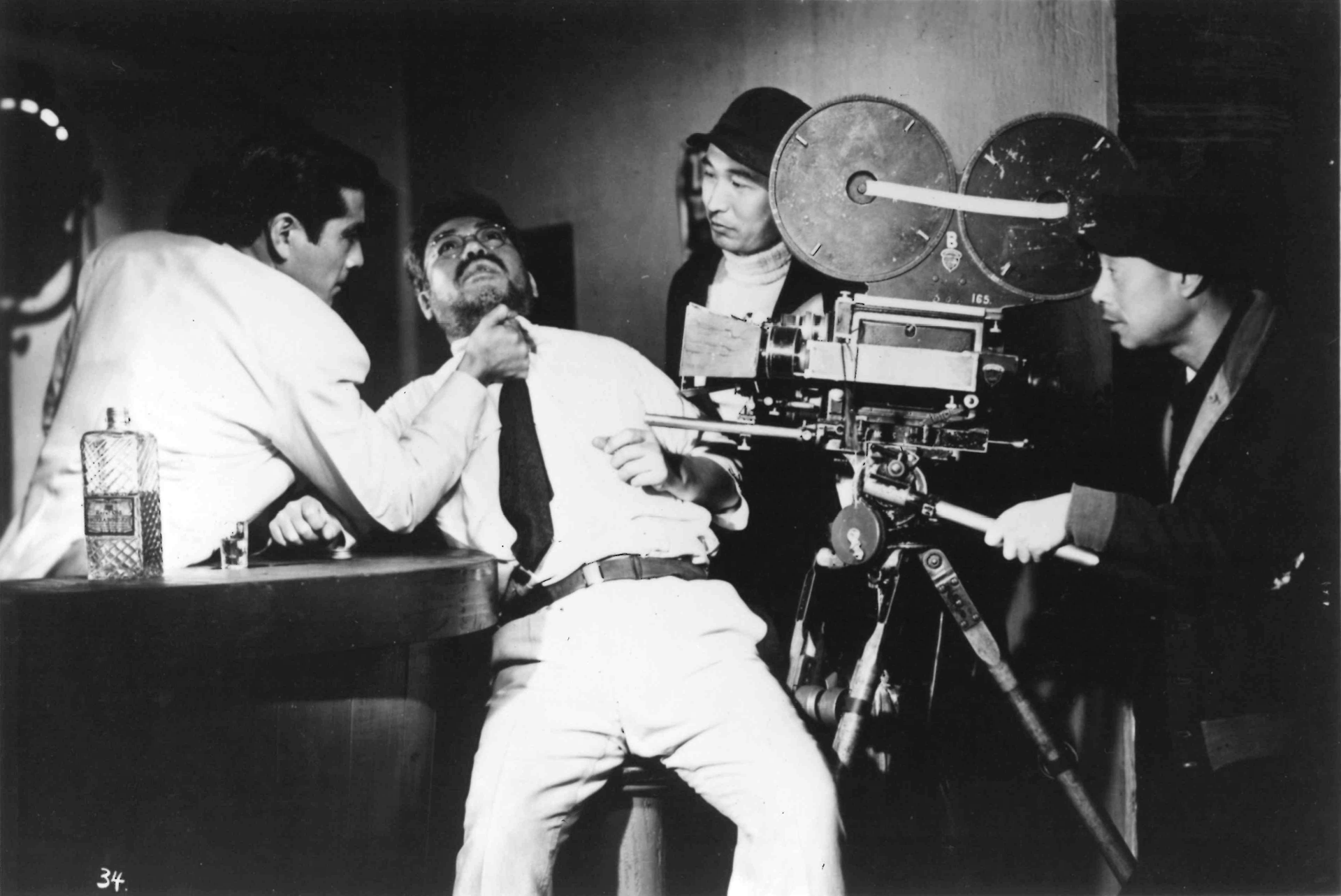

One winter day in 1948 when I was 24 years old, my friend, the late composer Fumio Hayasaka, took me to the Toho studios to watch the shooting of a film for which he was doing the score. They were filming in an elaborate open set, so detailed that it looked hardly different from the neighborhood outside the studio. A good-looking young man in a white suit and slicked-back hair was being directed by a very tall middle-aged man wearing a turtleneck sweater and a black, floppy hat. During a break Hayasaka introduced me. I then spoke no Japanese and they, with the exception of Hayasaka, spoke no English. After a halting conversation they then went back to work while I stood by the carefully detailed set and watched. The young man in a white suit was Toshiro Mifune, the tall man was Kurosawa, directing the young actor for the first time, and the film was Drunken Angel.

Akira Kurosawa (Center) filming Toshiro Mifune and Takashi Shimura in Drunken Angel (1948).

* * *

Spring 1954. I had just emerged from the first screening of the full Seven Samurai. Never had I seen a film like this—my eyes were watering, my ears still ringing. People were gathered talking, as they do when a film is clearly a success. Several clustered around a very tall man in a floppy blue hat, the same man I had met six years before. Hayasaka was nowhere around and I did not think I would be remembered. So, though I could speak some Japanese by then, I did not go and congratulate him as the others were doing. Instead, I stared at him and determined that I would do everything I could to get this film seen by everyone, everywhere.

* * *

Late autumn, 1956. Joe Anderson and I were in Izu at one of the open sets for Throne of Blood, Kurosawa’s adaptation of Macbeth. It was known that we were doing a book on the Japanese film and, further, that I would be writing about this particular film for the Japan Times. Work was running far behind schedule, Kurosawa having refused to use a completed set because it was constructed with nails and the long-distance lenses he was using might pick up the anachronistic nailheads. Both Joe and I were thrilled by this uncompromising courage. We had never known a director so conscientious. The present set represented the provincial palace of Lord Washizu, the Macbeth Character, and his return home was being filmed. Soldiers were in procession: banners, a stuffed boar, horses. When an assistant gave the signal the procession started forward under the late afternoon sun. Above us on a platform were Kurosawa and Asakazu Nakai, his cameraman. Earlier we had talked to the director and he had told us his plans for this scene. Now we were watching him do it. The entire afternoon was spent in starting and stopping the distant procession and photographing it. When we saw the finished picture the following January, not one of these shots was in it. We asked Kurosawa about it. “The scenes were nice enough,” he said, “but not really necessary. Besides, they interrupted the flow of the picture.” We marveled.

Kurosawa flanked by American film historians Donald Richie (Left) and Joseph Anderson (Right) on the set of Throne of Blood (1957).

* * *

Late summer 1958; at one of the open sets for The Hidden Fortress near Mt. Fuji. After a long day’s shooting, I was sharing a bath with Mifune. His body was very white from the neck down. From the neck up he was still wearing his makeup for General Rokurota Makabe. It had been a tough day, with the same scene shot over and over again. I had noticed that Kurosawa’s ball point pen would not work. Instead of throwing it away and getting another, he had all afternoon attempted (between takes) to make this pen, this particular ball point pen, work. I mentioned this, tactfully, to Mifune while we sat up to our necks in the hot water. “I know what you mean,” he said, “And I felt just like that ballpoint pen. But did you notice, he did finally get it to work.”

* * *

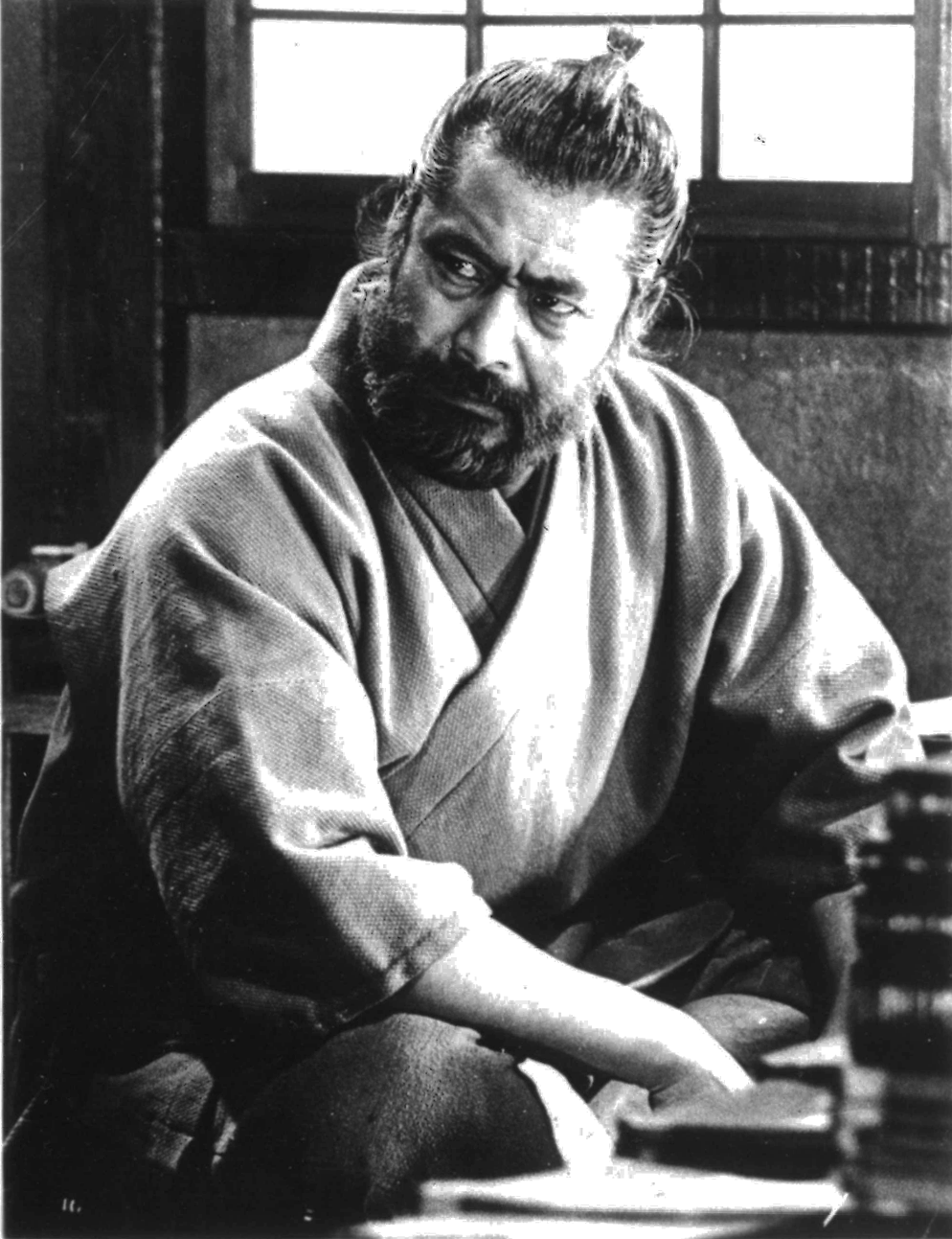

Left: Toshiro Mifune, star of 16 Kurosawa films, as Red Beard.

A cold winter day, 1964; on the studio set for Red Beard. The picture was over budget and long over production schedule. Not a happy day—snow—and Mifune, with other contractual obligations, was still in full beard and unable to fulfill any of them. It was known that I was writing a book on Kurosawa and that I could, with some discretion, talk to the director whenever he was free. He was sitting in a canvas chair and was wearing a white cap and dark glasses, now that his eyes were giving him trouble. He looked dejected. In an effort to make him feel better, and in order to have something to say, I told him he didn’t really look much different from the first time I had met him. Yes, he remembered that day, he said, way back in the days of Throne of Blood, with Mr. Anderson. No, I replied taken aback, back in the days of Drunken Angel, with the now long dead Mr. Hayasaka. He looked at me and frowned. On the Kurosawa set a mistake gets first, a frown, “I don’t remember that,” he said. He then set to work remembering. Nothing came of it, but I remembered the nails in the discarded set, the ballpoint pen that would not work, the unhappily bearded Mifune. We were problems—all of us—problems to be solved.

* * *

A summer day, 1978; cicadas. At the Toho studio at Seijo I was talking with Nonchan, Teruyo Nogami. Her name has never been in the credits of any of his films, yet since the days of One Wonderful Sunday in 1947 she has been with him, always there, the perfect liaison, always making certain that what he wants, what he needs, he gets. Of anyone, Nonchan is the closest to him, I don’t think he could function without her.

I had just read the script for Ran (“rebellion, riot”), his adaptation of King Lear, and was most enthusiastic about it, thinking it one of the best Kurosawa had ever done. Yes, she agreed—but the money… She was holding a number of color sketches and spread them out on the table for me to see—big, colorful, splashy pictures. “This is what he is doing now”, she said. Now, she did not add, that he had no money to make a film with, now that he believed that the only film would be in these drawings. They were all for something to be called Kagemusha, a project I had not heard of.

Later, I watched him work on the Kagemusha portfolio. With his large, capable craftsman hands, he was painting one picture after another. The movements were swift and sure, he always knew just what he was going to do. The entire film was in his head, emerging through his fingers. Since he had no money to make the picture on film, he was making it on paper. What other director, I wondered, would do this, would care this much, and would be this immune to despair?

As I looked at him I was struck once again by the disparity between his face and his hands, his head and his body. A workman’s body, very strong, and the hands of a craftsman. But the head is that of an ascetic, even more like a priest’s now that the hair is thin; the nose is large, the lips thin. The face is closed, indicative of great spiritual strength, like the faces in Zen paintings.

* * *

March 23, 1980; a Chinese restaurant near Seijo, It is Kurosawa’s 70th birthday—his family, his children, grandchildren, Nonchan, the staff and a few friends. Various birthday presents. But the best of all is the fact that Toho, George Lucas, Francis Coppola, and the residuals from Star Wars have made Kagemusha a reality.

I thought back to the 38-year-old director on the set of Drunken Angel in 1948. The intervening years had not made all that much difference—he wears caps now instead of floppy hats. I thought of the will that had created his films. Those big, strong hands were now delicately opening birthday presents, the fingers precise but very firm with unwilling knots, Kurosawa turned, smiled, and his great strong hand carefully smoothed the hair of a favorite grandson.

I thought too of that long gone ball point pen, worked until it forgot it was broken, until it began to write again.

Follow Japan Society Film on Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, or Letterboxd for more exciting deep dives into Japanese cinematic history! Founded in the early 70s, Japan Society’s illustrious film program has been the premier venue for the exhibition of new Japanese film as well as classic series and retrospectives. Over the years, Japan Society Film has hosted numerous high profile premieres and programs that include visits from Akira Kurosawa, Toshiro Mifune, Masahiro Shinoda, Shima Iwashita, Hideko Takamine, Tatsuya Nakadai and Nobuhiko Obayashi.