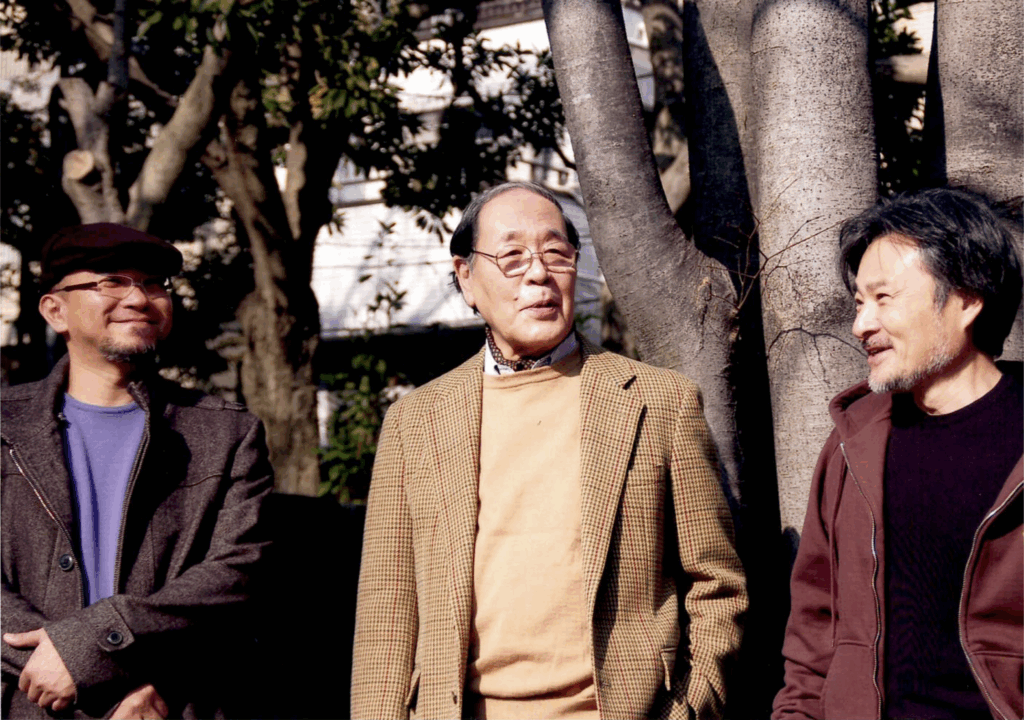

An Introduction to Shiguéhiko Hasumi

It’s hard to overstate the stature and influence of Shiguéhiko Hasumi in Japan. There’s no figure truly comparable in Western film culture—and yet, despite having made such a profound impact on Japanese cinema, Hasumi’s name and writings remain relatively obscure in the West. We took the opportunity to ask one of Hasumi’s former students, director Kiyoshi Kurosawa, to introduce the esteemed scholar to our audience.—Alexander Fee, Film Programmer

Shiguéhiko Hasumi burst onto the Japanese film journalism scene in the late 1970s to early 1980s, emerging as a brilliant and fresh new film critic. He made a tremendous impact not only on journalism but also on all the young film enthusiasts of the time, who were relentlessly experimenting with independent filmmaking. He is a figure who dramatically reshaped the course of Japanese cinema history. This is an undeniable fact, and I was right in the midst of it.

I first came to know Mr. Hasumi in the mid-1970s, through a film class at a private university, meeting him in the student-teacher context. At that time, Hasumi was still unknown to the general public, and I attended the class with little expectation, not knowing who he was. But as a result, not only did he change my perspective on cinema completely, he transformed my entire outlook on life—and his influence has stayed with me ever since.

Putting aside my own story, let me first delineate how the arrival of Shiguéhiko Hasumi forced a transformation in film journalism of the time. Above all else, Hasumi insisted: “Watch the film itself.” What truly exists in a film, he argued, is only what is actually shown on screen and what is audibly heard. Anything beyond that—the story, social relevance, the creator’s intention—no matter how eloquently discussed, is not the film. Those who focus on such things are not really watching the film at all; they are merely using the film as a tool to express unrelated personal opinions. Such talk does nothing to enrich cinema—in fact, it obstructs the viewer’s ability to see the film itself.

In practice, Hasumi would rapidly draw attention to things like recurring round objects in Hitchcock’s films, hands in Robert Bresson’s works, water in Don Siegel’s, or the absence of staircases in Yasujiro Ozu’s films. In doing so, he effectively swept aside the older generation of journalists who had long believed that proper film criticism consisted of analyzing plot, social significance, and authorial intent.

Of course, Hasumi’s discourse around cinema was not about elevating film to the level of high art. On the contrary—it was a declaration that film is a fierce, wild, and unknowable beast, and that anyone who looks at it directly must be prepared to have their previously comfortable worldview shattered. His was a call to open one’s eyes wide to the terrifying power that lies hidden in cinema itself.

What made Hasumi even more extraordinary was that his meticulously provocative and deeply thoughtful writings are lined with an astonishing array of film titles and director names from across time and around the world. It wasn’t abstract theory that captivated us, but rather this seemingly endless incantation of film titles—like a spell. We were enthralled above all by that.

To demonstrate how chaotic cinema truly is, he would bring Sam Peckinpah, Wim Wenders, Raoul Walsh, and Louis Lumière to the table. To speak of the purest works in film history, he would reference Sadao Yamanaka, Jean Vigo, and Richard Fleischer. Naturally, this made it impossible for us not to seek out the films of those directors. And since this was a time before DVDs or streaming, we would rush to repertory theaters and cine-clubs, determined not to miss a single shot, spending our days with eyes glued to the screen.

From the 1980s through the 1990s, it was perhaps inevitable that, among the young people who were devouring films under Hasumi’s immense influence, some would eventually emerge with serious ambitions to become filmmakers themselves. By this time, the old Japanese studio system had long since collapsed. Yet to keep theaters operating, the industry still had to produce a large number of films each year—resulting in a steady decline in the overall quality of Japanese cinema. Of course, there were still distinctive works, films rooted in bold social critique, and even major box office hits. But many of those films could not stand on their own unless they were wrapped in values external to cinema itself. In other words, the very raison d’être of film—especially for Japanese film—was increasingly fading away. The prevailing sense of the time was: even if film ceased to exist, no one would really be troubled by it.

Amidst all this, there were young film lovers who spent a great deal of time immersed in cinema, and who genuinely felt a sense of crisis—believing that if film were to disappear, it would be a profound loss to their lives. For them, Shiguéhiko Hasumi became a guiding figure, both in thought and action. It was these young people who sustained Japanese cinema through its near-death state in the 1980s and 1990s. In other words, the young cinephiles that Hasumi had inspired—driven not by profit, nor by artistic exploration, nor by social relevance, but by a pure desire to stay close to cinema, to understand what cinema truly is, to try anything that allowed them to be involved with film—began to speak about cinema in words they genuinely believed in. They even tried making films that resembled the kind of cinema they believed in. And it was precisely these actions that slowly transformed film journalism and commercial filmmaking, pushing Japanese cinema forward. This is an undeniable fact in the history of Japanese film.

Nearly thirty years have passed since then, and even today, it is clear that many of Japan’s active film critics, producers, cinematographers, and directors continue to be influenced by Hasumi in some form. Takeshi Kitano, Hirokazu Kore-eda, Naomi Kawase, Ryusuke Hamaguchi, Sho Miyake, Koji Fukada—each of them has built a remarkable career with their own distinct voice and talent. But had they never encountered the cinematic values Hasumi advocated, it’s likely their work would have taken a very different form. The international recognition of Yasujiro Ozu and Mikio Naruse would never have been achieved without Hasumi. Even the popularity of Clint Eastwood and Wim Wenders in Japan owes much to his influence. And as for myself—there’s no doubt that I’m only able to be here, doing what I do, all thanks to the good fortune of having met Shiguéhiko Hasumi.

Kiyoshi Kurosawa, September 2025

Shiguéhiko Hasumi: Another History of the Movie in America and Japan runs from October 9 – 18.

Translation by Mako Fukata